Over the past year I’ve been exploring various parts of The Hundred Years’ War, from Poitiers to Agincourt, from Verneuil to the exploits of Joan of Arc… but I wanted to more closely explore the battle that really started the ball rolling. Crécy. But where to start?

As it happens, I was recently recommended the Michael Livingston book Crécy: Battle Of Five Kings by my online pal and medieval scholar Stuart Ellis-Gorman (who himself wrote a fascinating book about crossbows that I’ll have to post a proper review of as well). Crécy: Battle Of Five Kings sets the stage for the battle by going way back to 1066 and revisiting the French invasion of England, then tracing the events that led to the dethroning of Edward II and the crowning of his 14 year old son, Edward III. Edward would later invade France and meet head-on with Phillippe of Valois, both of whom claimed to have the legitimate claim to the crown of France.

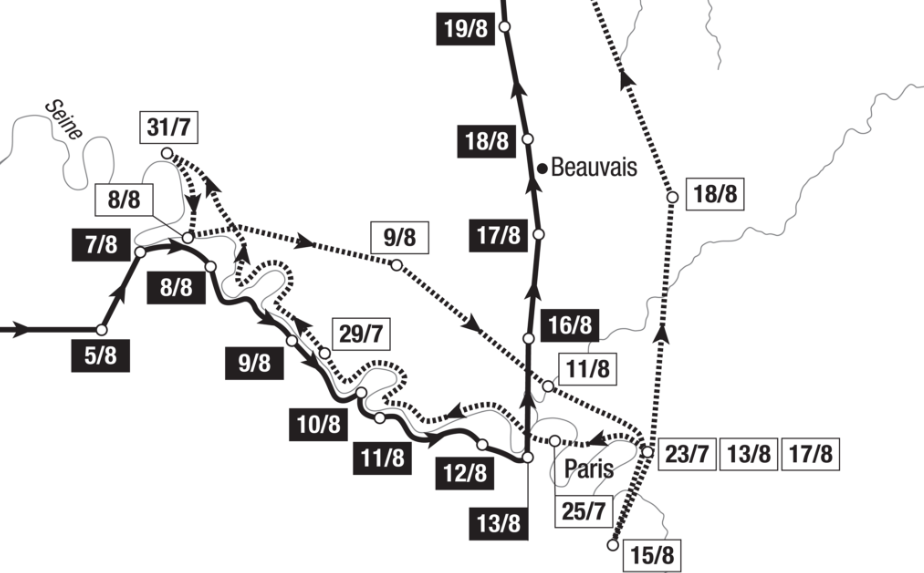

Edward invaded France several times but in July of 1346 he came in force, burning a fiery path across the countryside (a military technique known as a chevauchée), all the way to Poissy, a handful of kilometres from Paris, before running in to Phillippe’s army. The French chased the English almost 200km back to a small town Crécy-en-Ponthieu. It was here that the English finally stood their ground, creating a defensive structure from overturned wagons, called a wagenburg. By positioning them just so, they could effectively funnel the enemy toward them in a more controlled manner. The French onslaught was prolonged and they suffered massive casualties, while the English walked away relatively unscathed. It was a disastrous result for the French.

The exact site of the battle was long thought to have been known by historians, but Livingston together with historian Kelly DeVries have disputed the popular site through their own investigative work, placing it several kilometers away near the Crecy forest, in a location that appears to make much more sense. This type of independent legwork is one of the things I admire most about Crécy: Battle Of Five Kings, and some of the new information presented here come from the most unassuming of sources.

During 2020-21, I spent significantly less time reading and more time… doing stuff. I was furloughed from work due to the pandemic, and felt I needed to be physically productive, so I ended up building some things out of stone and wood. A lot of this I did with fairly rudimentary tools, and while chiselling some lap joints into a 6×6, I got to thinking about carpentry in the middle ages (as one does).

We of course remember the thousands of soldiers involved (the men-at-arms, archers, and spearmen), but few of us ever think about the huge support staff – such as the dozens of carpenters who came along on the campaign, or William Retford, a cook.

Retford’s “Kitchen Journal” is an unassuming piece of work, but as DeVries and Livingston discovered – it provides a valuable breadcrumb. During the campaign, Retford would be tasked with procuring the food and preparing the meals. The journal he kept contained all the receipts for these transactions, including (as receipts do) the details of what was purchased, how much it cost, when it was procured, and from where. Using this log, Livingston was able to pinpoint the location of Edwards army with precision during most of the campaign on any given day.

What I really enjoyed was the chapter “Reconstructing Battles” wherein Livingston describes his “toolkit” when researching historical battles. He begins by explaining how irrational battles are, which makes them difficult to track. He talks about how a battle is made up of thousands of individual decisions from soldiers who may or may not be around to talk about them after the fact. He then goes on to talk about the things he utilizes to tell the story, and his personal maxims when conducting research of this sort. Archaeology. Multiple Sources. Previous known tactics. The capabilities or limitations of the technology. All of this data can be fed into the model.

In the case of Crécy: Battle Of Five Kings, the result is a wonderfully vivid account that tells the story and, in some cases, retells it with a new and possibly more accurate angle. I learned a lot from this book about the early days of the Hundred Years War, and I highly recommend it to anyone with an interest in the Battle of Crécy.